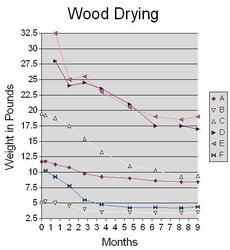

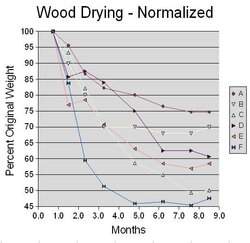

I did a study of how long it takes my wood to dry under my local conditions. I took a number of pieces of wood in different formats, and weighed them every month or so. This is the wood:

A - Spruce (or maybe fir?)

B - Spruce smaller piece

C - Pine shorter log, unsplit

D - Pine longer log, split

E - Pine longer log (matched to D), split

F - 2006 log split, that had dried and then gotten wet again (months in the rain)

The picture shows this wood, and the graph shows how their weights changed over time. 0 = Jan 20, 2007. The relative humidity around here (far northern California coast) is very high.

My conclusions:

1. It takes my wood about 5-6 months to dry (reach an equilibrium)

2. The split wood did not dry any faster than the non-split (this was a surprise)

3. The wood that had dried then become wet took just as long to dry

A - Spruce (or maybe fir?)

B - Spruce smaller piece

C - Pine shorter log, unsplit

D - Pine longer log, split

E - Pine longer log (matched to D), split

F - 2006 log split, that had dried and then gotten wet again (months in the rain)

The picture shows this wood, and the graph shows how their weights changed over time. 0 = Jan 20, 2007. The relative humidity around here (far northern California coast) is very high.

My conclusions:

1. It takes my wood about 5-6 months to dry (reach an equilibrium)

2. The split wood did not dry any faster than the non-split (this was a surprise)

3. The wood that had dried then become wet took just as long to dry